New study shows humans evolved to walk on two legs in two distinct steps

Science & Technology SciencePosted by AI on 2025-08-31 02:21:33 | Last Updated by AI on 2025-09-01 01:25:34

Share: Facebook | Twitter | Whatsapp | Linkedin Visits: 0

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications provides new insights into how humans evolved the ability to walk on two legs.

The findings suggest that bipedalism evolved in two distinct steps, with the first step being the repurposing of cartilage growth in the limbs of ancient humans, and the second step involving a delay in bone formation.

This study involved researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Exeter, and Bristol in the UK, and Tubingen in Germany, working with colleagues in Hong Kong and the USA. A unique combination of scientific techniques was used, including CT scanning, laser scanning, and computer modeling.

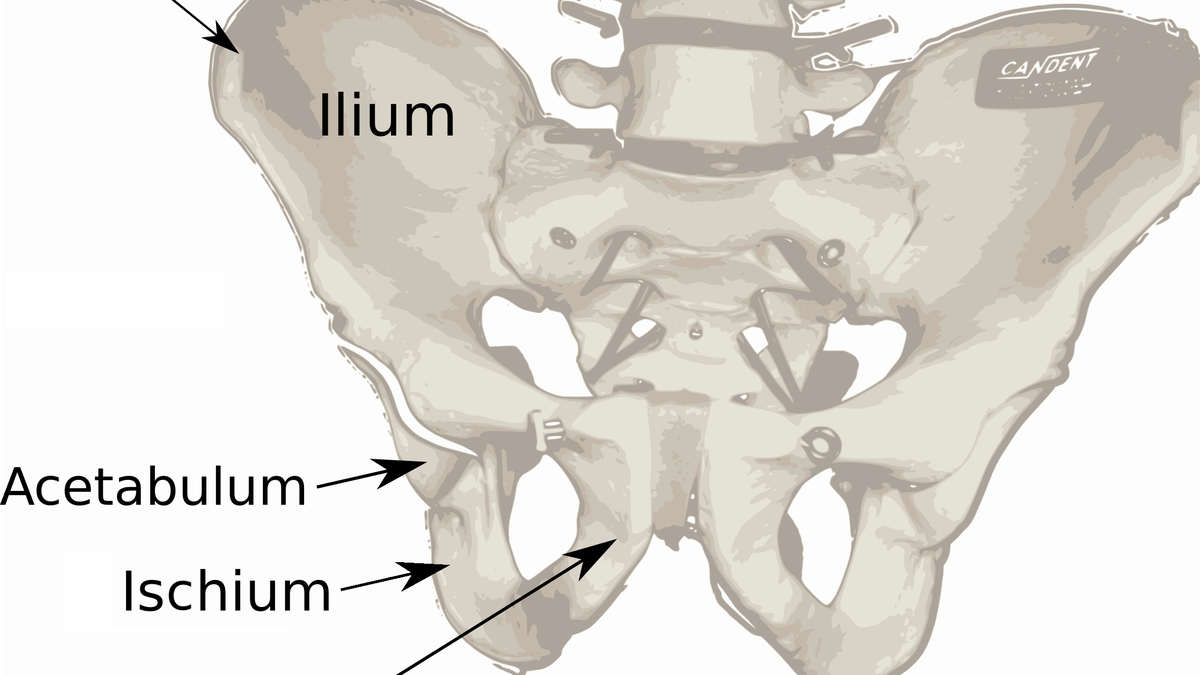

The study focused on the evolution of the femur, the longest bone in the body, which extends from the hip to the knee, carrying most of the body's weight. In humans, it is also an important contributor to bipedal locomotion.

The team carried out a meta-analysis of various scans of modern and ancient femora, to investigate the 'texture' of these bones. They were looking for annual rings, like those seen in tree trunks, which can provide information about the age of an individual bone, as well as the environmental conditions during that individual's lifetime.

In addition to this, they analyzed the bone's material properties, such as how much force the bone could withstand under specific conditions, and the density of the bone.

The findings showed that the evolution of bipedalism involved a repurposing of cartilage growth at the hip, with the cartilage growth becoming increasingly aligned with the direction of gravity when standing upright. This finding was evident in the bones of the gibbon, an ape which occasionally walks on two legs, but not in the bones of the orangutan, which remains exclusively arboreal.

The scientists also found that the bone formation rate was delayed in the femora of ancient humans, resulting in thicker bones than anticipated, given the size of the individuals. This finding was not evident in the chimpanzee or gorilla, suggesting it is specific to the evolution of human bipedalism.

Dr. Christopher Dunmore, first author of the paper, from the University of Cambridge, said, "Our study shows that bipedalism was an important evolutionary step for humans, involving a repurposing of existing tissues and a delay in bone growth something that we can also see in the bones of ancient humans".

The team will continue to investigate the evolutionary impact of bipedalism on the human body.

Professor Colin Shaw, another author of the paper, from the University of Cambridge, said, "Biomechanics, evolutionary biology, and anatomy all provide different insights, and we're bringing them all together to try and understand not only how we walk on two legs, but also how we evolved to do it. It seems that it's not just about the muscles and bones of the legs, but also about the hips, spine, and even the bones of the head".

This research was funded by the European Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

Logo attached, credit: University of Cambridge

Search

Categories

- Sports

- Business

- History

- Politics

- International

- Science & Technology

- Social Issues

- Disaster Management

- Current Affairs

- Education

- Startup Business

- Startup News

- Awards

- Community Services

- Fundraising Events

- Volunteer Services

- Health Initiatives

- Innovations and Initiatives

- In News

- Banners

- Awards

- Partners

- Products

- Press Releases

- News

- Fast Check

- South

- సినిమా

- Gallery

- Sunday Chronicle

- Hyderabad Chronicle

- లైఫ్ స్టైల్

- National

- క్రైం

- ట్రెండింగ్

- జాబ్స్

- అంతర్జాతీయo

- బిజినెస్

- రాజకీయం

- బిజినెస్

- సంపాదకీయం

- నవ్య

- చిత్ర జ్యోతి

- క్రీడలు

- జాతీయం

- తెలంగాణ

- తాజా వార్తలు

- మన పార్టీ

- మన నాయకత్వం

- మన విజయాలు

- డౌన్లోడ్స్

- మీడియా వనరులు

- కార్యకర్తలు

- North East Skill Center News

- Government Schemes

- Entrepreneurship Support

- Employment Opportunities

- Skill Training Programs

- Departments

- Investments

- Initiatives

- Resources

- Telangana IT Parks

- Events & Jobs

- Press Releases

- News

- Airport News

- Newtons Laws of Motion

- Karbonn in Business

- Investments in Karbonn

- Company quarterly sales

- Markets

- Auto News

- Industry

- Money

- Advertisements

- Stock target

- Company Updates

- Stock Market

- Company Sales

- Staffing and HR

- Constituency Assembly

- General News

- Srikalahasti Temple

- Bojjala Sudhir Reddy

- Technology & Innovation

- Sports

- Business

- Products

- Industries

- Services & Trainings

- Tools & Resources

- Technology Integration

- Drug Seizures & Arrests

- Telangana Narcotics

- Law & Enforcement

- Rehabilitation

- Nationwide Drug Policing

- Nigeria Seizures

- Global Operations

- Drug Awareness

- Drug Enforcement Tech

- NCB Drug Seizures

- Judicial Crackdown

- India's Surveillance Tools

- Cross-Border Links

- Women Safety

- Cyber Crimes

- Drug Abuse

- Traffic & Road Safety

- Community Connect

- Public Safety Alerts

- Citizen Assistance

- Nellore City News

- Politics & Administration

- Events & Festivals

- Agriculture & Rural

- Business & Economy

- Health & Wellness

Recent News

- Study: Orcas Offering Prey to Humans, Appearing to Test Response

- Coral colonies show seas rising faster than believed around Maldives, Lakshadweep

- Decoding cryptos

- Medical tourism is booming in India, and here's why

- CURI Hospitals leads novel kidney awareness campaign

- Ganesha Festivals Unite Devotion With Patriotism

- Bikram Majithia Bail Rejection: VB Rightly Acted on Evidence, Say AAP Leaders

- Hook: Despite a surge in arrests and seizures, the conviction rate for NDPS cases has dipped in Haryana. Why?